- Home page

- What were you doing out there on Highway 61?

- Why did you dig there?

- Where is the site?

- Who lived there?

- What happens after the digging?

- What is archaeology?

- What is it like to work on a field crew?

- What is it like to work in the lab?

- Are there laws that protect archaeological sites?

- Ask a Native American about tribal history, archaeology, and more

- Who can I contact for more information?

- Special pages for students

- Special pages for teachers

- Special pages for archaeologists

Answering your questions

What is the Leake site and why is it significant?

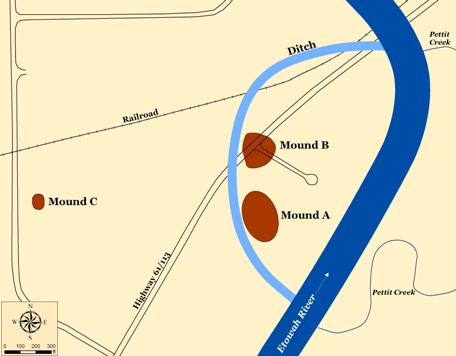

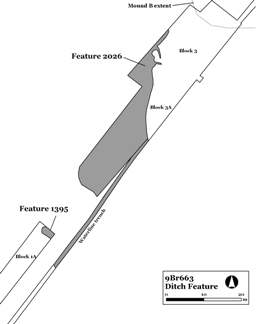

The Leake site is a Native American archaeological site that is located along the Etowah River southwest of Cartersville, Georgia in Bartow County. The site contains the remains of an American Indian occupation that lasted from approximately 300 B.C. until 650 A.D. These remains include three earthen mounds and a large circular ditch, along with an extensive "midden" that represents a dark soil mixture of decomposed organic refuse and artifacts. The site was excavated in advance of the widening of State Highway 61/113, with over 50,000 square feet excavated.The Leake site archaeological investigation revealed that this site represents a major center during the prehistoric Middle Woodland period, figuring prominently in the interaction among peoples from throughout the Southeastern and the Midwestern United States.

Map of the Leake Site.

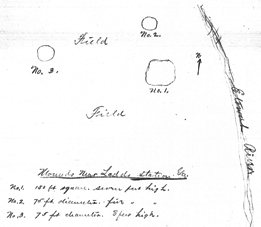

The Leake site was initially recorded in the late 1800s by Smithsonian Institution researchers under the supervision of Cyrus Thomas. James Middleton and John Rogan each produced maps of Leake, depicting three mounds; Rogan also excavated a portion of Mound B. Unfortunately, the earthen mounds at Leake were razed in the 1940s for use as road fill when the Dallas - Rockmart Road (State Highway 61/113) was moved to its present location, so that we know relatively little about the later stages of the mounds. However, the lower portions of the mounds remain, and have provided important information regarding their time of construction and usage. In addition to what has been found through archaeological excavation, historic maps, descriptions, and photographs of the Leake site have been very helpful in reconstructing the layout of the Leake site.

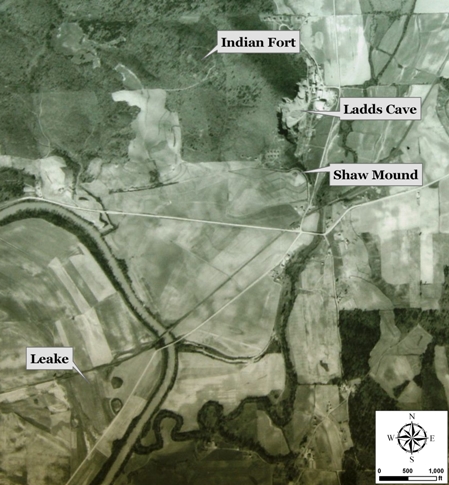

Annotated 1938 Aerial Photograph Showing the Leake Site Prior to Razing of Mounds.

Beginning around 300 B.C., local people began to live at the Leake site, similar to the numerous other villages that dotted the Etowah Valley at this time. During the next few centuries, the construction of the monumental earthworks began. In particular, we know that the early stages of Mound B and at least a portion of the ditch was constructed. It appears that the ditch was an old channel of the Etowah River that was modified by the occupants. While most of the pottery and other remains from the early occupation represent local products, the minority presence of non-local items indicates that peoples from other parts of the Eastern U.S. were visiting the site and/or that locals were bringing back foreign materials from their journeys. We have identified pottery from the Gulf Coast and northern Mississippi/Alabama, while a small fragment of copper may derive from the Great Lakes region. These materials were recovered from an area near Mound B that is indicative of group/communal activities. Such activities appear to have been focused around the construction of the earthworks and the rituals associated with this.

1917 photograph of Leake Mound B taken from northern edge of Mound A. Note summit of Ladds Mountain in right background and railroad trestle over Etowah River at center-right.

Around 100 A.D., the occupation of the site shifts west/southwest from inside the area created by the ditch to outside of the ditch area. This shift coincides with the appearance of Swift Creek complicated stamped pottery, a ceramic type characterized by elaborate designs that were impressed into the exterior of the vessels (see here for images of this pottery). Swift Creek pottery is found throughout most of Georgia and portions of the surrounding states; Leake is located at the northern edge of its distribution. In addition to the Swift Creek pottery, the amount of non-local and ritual items and raw materials drastically increases at this time. This includes flake blades of Flint Ridge chert from Ohio; pottery from the Gulf Coast; ceramic human and animal figurines; quartz crystals; graphite; copper; galena; mica; and hematite. Many of these items are representative of participation within the Hopewell interaction sphere, in which populations from throughout the Eastern U.S. interacted in social, econonic, political, and religious contexts. Similar to today, people and groups made long-distance journeys and pilgrimages to centers and places imbued with powerful cultural significance. It is generally believed that rituals and ceremonies were conducted at such sites, particularly in relation to the earthworks. Based on its monumental earthworks, Leake was such a place.

By approximately 400 A.D., the Leake site had expanded even further to the west/southwest. A large square structure was built in this area, measuring approximately 35' on a side and encompassing nearly 1200 square feet. The remains in the area suggest that this structure was used for communal/group activities rather than as a domestic house. Nearby was found the remains of a large feast, including deer, turkey, bird, and turtle. Artifacts from this feasting pit include many socially-valuable and exotic materials that indicate a strong connection to the Gulf Coast, such as a shark tooth and pottery from that area. The context of these artifacts suggest that they were used and discarded in a display of the sponsor(s) social connections and prestige. Sometime around 650 A.D., the Leake site was abandoned, not to be reoccupied until circa 1500 towards the end of what archaeologists call the Mississippian period.

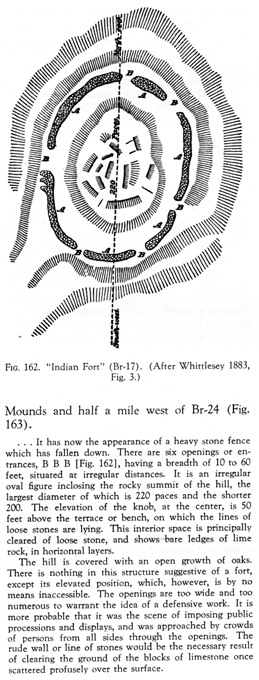

Just across the Etowah River on the nearby Ladds Mountain are several significant sites - Shaw Mound, Indian Fort, and Ladds Cave - that were integrally related to the Leake site. All of these sites were also documented by the Smithsonian Institution researchers at the same time as Leake. Ladds Cave was found to have been sealed with stones, and both animal fossils and human bones were recorded within its depths. The "Indian Fort" on the summit of Ladds Mountain was a circular stone wall/enclosure that was mapped and described by Charles Whittlesey in 1881. While the name "Indian Fort" implies that it was a defensive fortification, it rather represented an enclosure that would have served as a place for ceremonial activities. This site was dismantled in 1936 so that the stone could be used for road fill.

Annotated 1938 Aerial Photograph Showing the Leake Site and the Ladds Mountain Sites.

1936 Photograph showing the dismantling of Indian Fort. Individual in white in left of photograph is National Park Service archaeologist Calvin Johnson. Note that he is documenting this effort; attempts to find any surviving documents from this effort have not been successful.

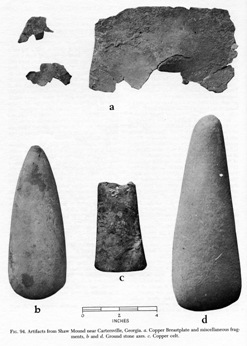

The Shaw Mound was a stone burial mound at the foot of Ladds Mountain that was dismantled circa 1940 to collect the stones for road fill and to satisfy the curiousity of the landowner. A single individual was found within, buried with several items of copper, including a celt (axe), breastplate, and a cutout; large sheets of mica atop the face and chest; and stone celts. Scraps from the production of such items are abundant at the Leake site. This burial provides significant information regarding the social system that characterized the local cultures. Buried apart from others in a large mound at the foot of this mountain, this personage was most certainly a prominent leader associated with the Leake site. They may be equated with a "Big Man/Woman", a person who has risen to a position of high social prestige and power through their actions rather than through inheritance. They were probably instrumental in the ceremonial, political, and economic happenings at Leake, such as organizing and supporting the construction of the earthworks.

1936 Photograph of Shaw Mound in the midst of a corn field. Shaw Mound is visible as the rise in the center, while the mined face of Ladds Mountain and Ladds Lime Works Company buildings are on the left. Ladds Cave was located in the area of the mountain that has been mined away.

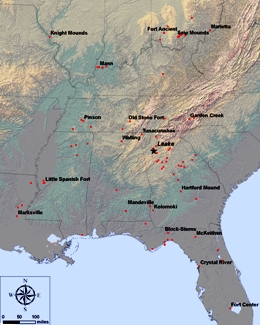

The presence of Ladds Cave, absent now due to mining, was likely to have been a primary factor in the development of the Leake site; caves are known to have been symbolic of the Lower World to Southeastern Indians, and burials and other evidence for ritual activities during this time have been found in caves throughout the Southeast. Along with this, the geological and geographical setting helped to fuel its rapid growth. Due to the rich and diverse geology, rocks and minerals that were used to create items of high social value - mica, graphite, quartz crystal, hematite, red ochre - were readily available in the area. Furthermore, the physiographic setting near the interface of several major river valleys (i.e., Tennessee, Chattahoochee/Apalachicola, Coosa, Ocmulgee/Altamaha) connected this location to the Gulf Coast, Atlantic Coast, and the Midwest.This setting and the archaeological remains found at Leake indicate that the site was a "gateway" between the Southeast and the Midwest. Leake served as a pilgrimage center, as a staging ground during the preparation for journeys, as a residential village, and as a place of ceremonies and religious worship.

Map showing major river systems in relation to the Leake site.

The precise reasons for the abandonment of the Leake site circa 650 A.D. are unknown, although it coincides with a regional shift in settlement and political organization patterns. Swift Creek pottery continues to be made in other areas of the state, such as central and northeastern Georgia, but it is generally lacking in northwest Georgia beyond this date. It may be that the communal ideology of the Swift Creek followers did not fit with the emergence of a more inegalitarian social system that came into full bloom in the Mississippian period, so that this social system based on communal support essentially eroded. It may be that the economic resources necessary to support large gatherings of people were depleted over the several centuries of occupation. It may be due to factors not readily identifiable in the archaeological record. Although the monumental earthworks constructed by these people are no longer visible, the Leake site complex is every bit as fascinating and important as the younger Etowah Mounds that lie 2 miles upstream. The archaeological investigations of the Leake site have provided answers to many questions regarding the activities of people during this period of time; at the same time, they have raised many additional questions which researchers will attempt to answer for decades to come. And like the Etowah Mounds, the significance of the Leake site argues for the protection of its remaining portions so that all people can share in this history.

1938 Aerial Photograph Showing Leake and the Etowah Mounds.

The Leake Site Area.

Selected Middle Woodland sites in the Eastern U.S.

1880s Map of Leake by James D. Middleton.

1943 Aerial Photograph Showing Placement of New Road and Razing of Mounds.

Grayed areas represent the ditch in archaeological context.

Soil profile showing early stage of Mound B and the underlying dark midden soil.

Reconstructed Swift Creek Complicated Stamped ceramic bowl.

Prismatic Blade of Ohio Flint Ridge Chert.

Ceramic Human Figurines.

Ceramic Duck Figurines.

Quartz Crystals.

Quartz Crystal modified into a pendant. (Note: this is crystal in lower left of picture above).

1883 Map & Description of Indian Fort by Charles Whittlesey (from Wauchope 1966).

Artifacts from the Shaw Mound. (From Waring 1945).

Recent photograph of copper breastplate seen in picture above. (This artifact is curated at the Antonio J. Waring, Jr. Archaeological Laboratory, University of West Georgia).

1936 photograph of person standing on top of Shaw Mound. This person appears to be National Park Service archaeologist Calvin Johnson.

1936 photograph of portion of Shaw Mound. Note the fedora in lower right corner.

Geological Formation at Ladds Cave Remnant.