- Home page

- What were you doing out there on Highway 61?

- Why did you dig there?

- Where is the site?

- Who lived there?

- What happens after the digging?

- What is archaeology?

- What is it like to work on a field crew?

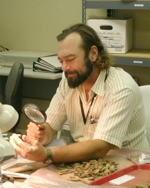

- What is it like to work in the lab?

- Are there laws that protect archaeological sites?

- Ask a Native American about tribal history, archaeology, and more

- Who can I contact for more information?

- Special pages for students

- Special pages for teachers

- Special pages for archaeologists

Crew journal

A day at work in the Leake Site lab

by J. T. Patton

Archaeological Technician

It is a brisk, sunny October morning when you arrive at the Southern Research headquarters. It's 9:00am and there are already three cars in the parking area. Debra Wells, the Lab Director, Conservator, Graphics Specialist, and Facilities Manager, is checking over trays of artifacts that have been sorted by the lab technicians, doing quality control as well as looking for mends (potsherds that fit together). Senior Archeologist Scot Keith is at his computer, researching and writing about a variety of subjects related to the Leake Site and its contemporaries. Jamie Barrow is at his computer as well, converting field maps and drawings into a computer graphics program that will give a detailed, comprehensive "big picture" of the Leake Site with all of its components and features.

It is a brisk, sunny October morning when you arrive at the Southern Research headquarters. It's 9:00am and there are already three cars in the parking area. Debra Wells, the Lab Director, Conservator, Graphics Specialist, and Facilities Manager, is checking over trays of artifacts that have been sorted by the lab technicians, doing quality control as well as looking for mends (potsherds that fit together). Senior Archeologist Scot Keith is at his computer, researching and writing about a variety of subjects related to the Leake Site and its contemporaries. Jamie Barrow is at his computer as well, converting field maps and drawings into a computer graphics program that will give a detailed, comprehensive "big picture" of the Leake Site with all of its components and features.

The lab side of the building consists of a spacious workroom with a hallway leading to the wet lab (so called because it is where the sinks for washing artifacts are located). Two walls of the workroom, two walls of the wet lab, and an entire wall of the hallway are lined with shelves full from floor to ceiling with labeled white boxes. These boxes contain some of the artifacts recovered from the Leake project. Looking at all of the boxes, you take a deep breath, realizing that they, along with the field notebooks, hold the data from eleven months of hard work. You know this because you were there. The fieldwork is over and now there is the challenge of organizing, analyzing, integrating, and interpreting all of that data.

You go to the wet lab and find a tall metal tray rack on wheels. The rack holds a number of rectangular, cafeteria-type trays, on which are collections of artifacts, mostly pottery sherds, each with its provenience carefully marked (provenience refers to where the artifacts were discovered back at the site: in which test unit, at what depth, etc. Artifacts without provenience are practically worthless to archeologists). These sherds have been arranged in groups according to size and decoration style. You carefully roll the tray rack down the hallway to the workroom. A sudden jolt could mix the separated sherds on the trays, and you don't want to have to sort them twice. You park the rack near your workstation. The workstations are a group of long tables in the center of the room. Your co-workers, June Williams and Shanna Bolcen, are seated there. They are Columbus State University students working in the lab part-time. June is labeling a group of potsherds with provenience information, writing the numbers directly onto the artifacts with a special fine-tipped conservator's pen. Only those artifacts with diagnostic designs (designs that help archaeologists determine when and where these items were made and who made them) or rims or bases that can be used to determine minimum vessel count are pulled and labeled in this way. Shanna is mending, the jigsaw-puzzle job of fitting sherds from the same vessel together and gluing them. Mending sherds together helps to determine the shape and therefore the function or use of the pot. The rack by your workstation is only about half full and your task this morning is to fill it up, so you pull a sealed plastic bag full of sherds from one of the boxes on the shelf. You put an empty tray on the table and place the stack of U.S.A. Standard testing sieves on it. These sieves are constructed of round brass bodies and stainless steel mesh bottoms of different sizes. They are made to stack onto one another. The sizes of mesh, in descending order are: 1 1/2 inch, 1 inch, 3/4 inch, 1/2 inch, and 1/4 inch. You gently pour the bag of sherds into the sieves. All but a few go through the top sieve, so you take those few, put them in a pile on a tray, remove the top sieve and gently stir the sherds in the next sieve. Again, the sherds that are smaller than that mesh fall through. The end result is five piles of sherds, separated by size. That's half the job. Now you will separate each pile by decoration type: Simple Stamped, Complicated Stamped, Check Stamped, Plain (non-decorated), et cetera. You hold each sherd up to a small desk lamp, turning it this way and that. Some of the designs are so faint that you will only see them when the light hits the sherd at a certain angle.

As you are working, Kay Wood, the President of the company comes in and shares a humorous anecdote from her recent fieldwork in South Carolina with the lab crew. Dean Wood, the Principal Investigator, has a story as well, from his recent presentation about the Leake Project at the Society for Georgia Archeology conference in Athens. Scot Keith emerges from his office, obviously excited about something. He shows us an illustration of a decorated ceramic bowl. He has found a match: one of the more unusual sherds from Leake is of the same design. The bowl in the illustration was recovered from the Tidwell mound site, "far" away in Northern Mississippi.

When you have your bag of sherds completely separated by size and type, with each pile labeled accordingly, you put the trays on the rack and get another bag from the storage boxes. The separated trays will be checked by Debra, all "mends" will be glued together and all artifacts that are pulled out of their provenience group must be directly labeled, as June is doing, after which you will bag each group and weigh them on a digital scale. Finally, the bags of separated artifacts go back into their storage box and that provenience is marked "done" for now. Before you know it, it is time to close the lab and leave. As you walk out the door you wonder again about the Middle Woodland world and which of its secrets these precious remnants will reveal.